Warning: Spoilers ahead. It’s best to read this piece after having watched the film.

Warning: Spoilers ahead. It’s best to read this piece after having watched the film.

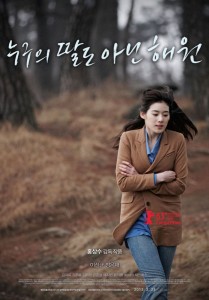

Nobody’s Daughter Haewon is a gently comic look at its protagonist, Haewon, a young acting student. Through the film, Haewon is shown sharing a warm relationship with her mother, being pursued by successful older men, being hated by her friends for being rich and aristocratic (neither of which she actually is, though she might wish to have been), while almost everyone repeatedly tells her how pretty, and what a good, brave person she is. Her married ex-lover and teacher Professor Lee still loves her, and throws jealous fits when he gets to know she has slept with others when they were not dating. (Professor Lee is the one who had broken off the relationship.) Eventually he is ready to leave his family for her, but Haewon, being wise, breaks it off, while he sheds copious tears.

She also somewhat ‘reluctantly’ lets out the secret of her affair with Professor Lee to her friends (in fact, she is dying to tell people about it; perhaps it feels claustrophobic to keep it to herself), and a miracle too happens in the course of the film with “mind control”, while her accomplished suitor has a chat with, implausibly enough, Martin Scorsese. Intercut throughout these scenes are shots of Haewon either sleeping or writing.

Most, if not the entire film, is Haewon’s daydream, or perhaps the class assignment to “prepare two scenes” that her fellow student informs her about. The hint, that Haewon is a compulsive dreamer, is given in the first scene itself, when, out of the blue, she bumps into Jane Birkin who, surprisingly enough, tells Haewon she resembles her daughter, the singer and actress Charlotte Gainsbourg. Haewon confesses she would do anything to be like Gainsbourg. In fact it’s as if Haewon wishes she were someone else, perhaps Charlotte Gainsbourg herself, while wishing Jane Birkin to be her mother. Once it’s made clear this was a daydream, we cut to the same location, the street where Jane Birkin walked, and see another woman, in similar colored clothes as Birkin. But this woman is Asian, shorter, different, and turns out to be Haewon’s practically estranged mother. (They haven’t met for five years.) Haewon’s idealistic fantasies explain just how lonely she really is — she is nobody’s daughter.

One of the best bits I liked about the film are the clumsy, amateurish, and at times rather randomly motivated zooms and pans. The film, as I said earlier, seems to be largely another film, set inside the aspiring actress Haewon’s head. There’s a running gag on smoking and unextinguished cigarettes lying on the road — perhaps a funny and rather pointless effort at symbolism by the young film school student. In between there are meditations on how all secrets are revealed by death, (“Death resolves all”), perhaps the kind of ruminations expected from a young artist. The film itself holds the opposite to be true — death only shrouds everything in secrecy. We know nothing about the lives of the men who built the fort Haewon frequents.

Only in the end do we realize that much, if not all, the film is a fantasy (or a film school assignment). And it would perhaps require a second viewing to see how the scenes, with all their carefully realized nuances, are actually in Haewon’s head. It is significant perhaps, that Haewon is an actress, someone who constantly needs to be somebody else. There is gentle, ironic comedy at her expense, and a sense of her loneliness and sadness, and one almost feels like patting Haewon on the head and saying, “There, there.”